Recently we built a linear particle accelerator to shoot lithium ions into a metal foil target to study warm dense matter as part of fusion energy research. In the heart of the accelerator are a series of high field pulsed solenoid magnets spaced apart along the length of the accelerator. These magnets are used to shape and kick the beam as it moves along the machine. For the function of the machine these magnets (27) all had to be very accurately aligned to one another and to the machine as a whole.

To compound the difficulty of aligning these solenoids they are inside an atmospheric pressure chamber buried deep inside a high vacuum chamber. Alignment, or even adjustment of the magnets after the machine was assembled would be impossible. The only choice was to align the magnets accurately prior to sealing them up inside the machine.

To start the process we built a special machine to measure the exact center of the magnetic field of each of the magnets before we sealed them up inside the machine forever. During winding and epoxy potting of the magnets small tolerances stack up to make each magnet somewhat unique. Each of the magnets was installed in its own special housing that also had small differences adding to a system error or offset. The magnet measuring machine uses a stretched wire that passes through the solenoid opening. The magnet is pulsed during testing which caused the wire to vibrated with a waveform we can analyze. The wire can be moved in space until the exact magnetic center is found nulling the vibrations. The basic problem is the magnetic center is not necessarily at the same position as the mechanical center of the physical magnet.

Now here is the trick part. Because we know where the wire is precisely, determined by using a laser diodes and micrometers to sense the wire. We can now transfer those measurements to the physical part of the support structure that houses the magnets and align the magnet accurately to the structure. Over forty feet our alignment target was a cylindrical tube shaped tolerance zone one millimeter in diameter. When I describe the problem to non technical folks I ask them to imagine aligning 30 individual pencil in space in almost all spatial orientations X, Y, Z pitch, yaw with a foot between each pencil and have them place a dot on a piece of paper within a circle one millimeter in diameter.

Each magnet had to be aligned to a angular tolerance of ten milliradians or less in tilt and less than 30 microns in X and Y. To provide alignment adjustment there is a system of flexures that are used to align the magnets for tilt and XY displacement. All this is pretty straightforward until you find out there are large magnetic forces axially along the solenoid axis when each magnet pulses. This force was calculated to be around 900 lbs.

Here is where our machining problem comes in. We needed end spacers to trap the magnet axially in its cavity to prevent it from moving. The spacers needed to be accurate in thickness and have a very specific angle machined into them to match the tilt error of each solenoid and housing. To make it even more interesting the spacers were round to fit the end of the solenoid magnets. What this added to the mix was a radial orientation that had to match.

To do this job we used a special tilt table that I built many years ago. Angle setups are among the most difficult and demanding jobs that most machinists encounter. If your angular setup is not perfect the results will be sub-optimal. I personally use the sine bar for many of my angular setups because they are easy to use and very accurate. In the case of these special spacers the angles were very small, on the order of one tenth of a degree. The sine bar can easily handle small angles like this but the work holding part of the job made it a better job for the tilt table. One problem with sine bars is the limited options for mounting parts directly to them for machining. Somebody out there invent a Kurt vise that has sine rolls built into the bottom and a good way to lock it to the table for real machine work.

The scientist taking the measurements gave us the angular data as a dimension over a distance with a radial clocking reference. So we might get numbers like .015 inches over the diameter of the spacer which was 8.5 inches. Saying it another way is .015/8.5 which describes the angle enough for machining. Using the tilt table its a simple matter to set this angle using a dial indicator and a parallel.

The angle is set by traversing along the parallel a fixed distance (in this case 8.5) and noting the indicator displacement. The angle is adjusted by turning rest screws that bear against the top of the vise.

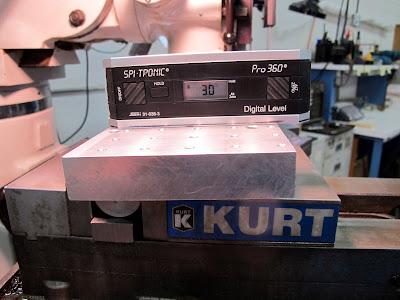

In this shot you can see how the tilt table works. A steel rod is attached to the table working surface and clamped in the vise. The table can pivot on this rod to angles up to around fifty degrees from the horizontal. Obviously the rest screws will not touch at those high angles. There are a several ways to set an angle using the tilt table. In addition to the method above using an indicator to measure along a fixed distance angle blocks and electronic levels can be used depending on accuracy needs.

The underside of the tilt table showing the clamp and pivot rod attachment to the plate.

Setting a quick angle with an electronic level. This particular level has the ability to re-set the origin on any reference surface.

Because the top surface of the tilt table is festooned with tapped holes I can use it with the mini pallet strap clamps for a variety of workholding options. I find it most useful for longer low angle work such as doctor blades or single bevel cutting edges. The table is most stable when set to a low angle and its long clamping surface provides lots of holding options for the work.

Thanks for looking.